There are architectures and patterns that look cool on paper, and there are ones that are good in practice. Implementing the hexagonal architecture with Camel is both: cool to talk about, and a natural implementation outcome. I love going hexagonal with Camel because it is one of these combinations where the architecture and the tool come together naturally, and many end up doing it without realizing it. Let’s see why that is the case.

Why go Hexagonal?

Hexagonal architecture is originally described by Alistair Cockburn as an approach for dividing an application into inside and outside parts. Its intent is to move focus from multiple conceptual layers of an application to a distinction between the inside and outside parts of the application. The inside part represents the domain layer or the business logic, and the outside part consists of all the possible incoming or outgoing interaction points of the application. The same architecture is also known as Ports and Adapters as the connection between the inside and the outside of the application is realized through ports and adapters.

The word "port" is inspired by the operating system's ports where any application that conforms to the protocol of a port can send or receive signals from an application. In a sense, a port represents a purposeful conversation. And the adapters represent the technology-specific implementations of a port. Depending on the business benefits offered through the port, there might be multiple adapters that would like to expose the port using different technologies.

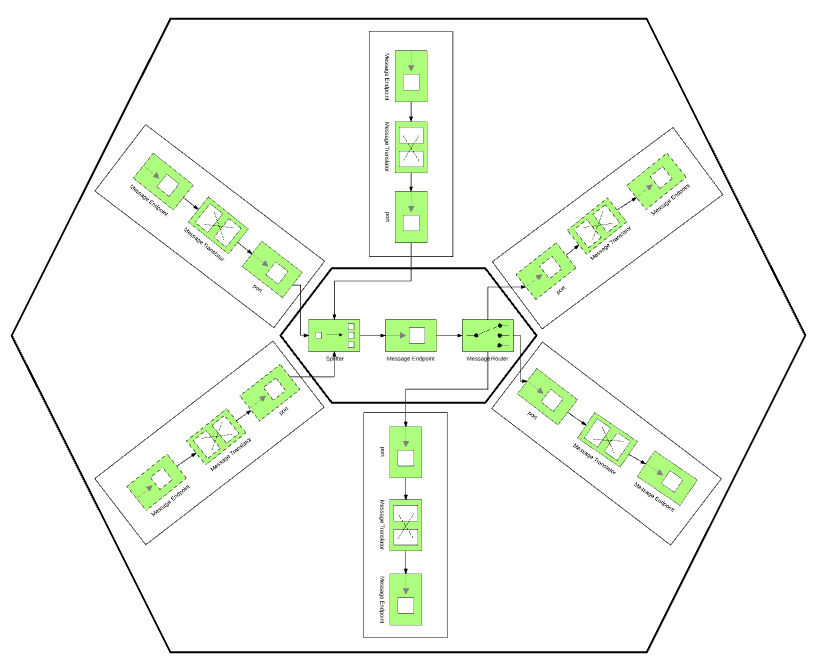

Hexagonal architecture visualized with Camel routes

Notice that all ports and adapters are fundamentally similar at the architectural level, but Alistair acknowledges that the ports and adapters come up in two flavors: primary and secondary or driving and driven. For example, if there is a simple REST based service that reads and writes to a database, the REST side of the service would be the primary actor port and adapter as it initiates and drives the interactions. The port and adapter for writing to the database side would be the secondary and driven actor as it is not initiating any calls (assuming we are not using any data change capture listeners in which case this adapter would also be a primary one).

Briefly said, hexagonal architecture helps us avoid multi-layered architectures that are prone to end up being baklava architecture (anti-pattern). Instead, it pushes us towards simplified separation of concerns, and onion-architecture, clean architecture, and similar.

Why is Camel Hexagonal in Nature?

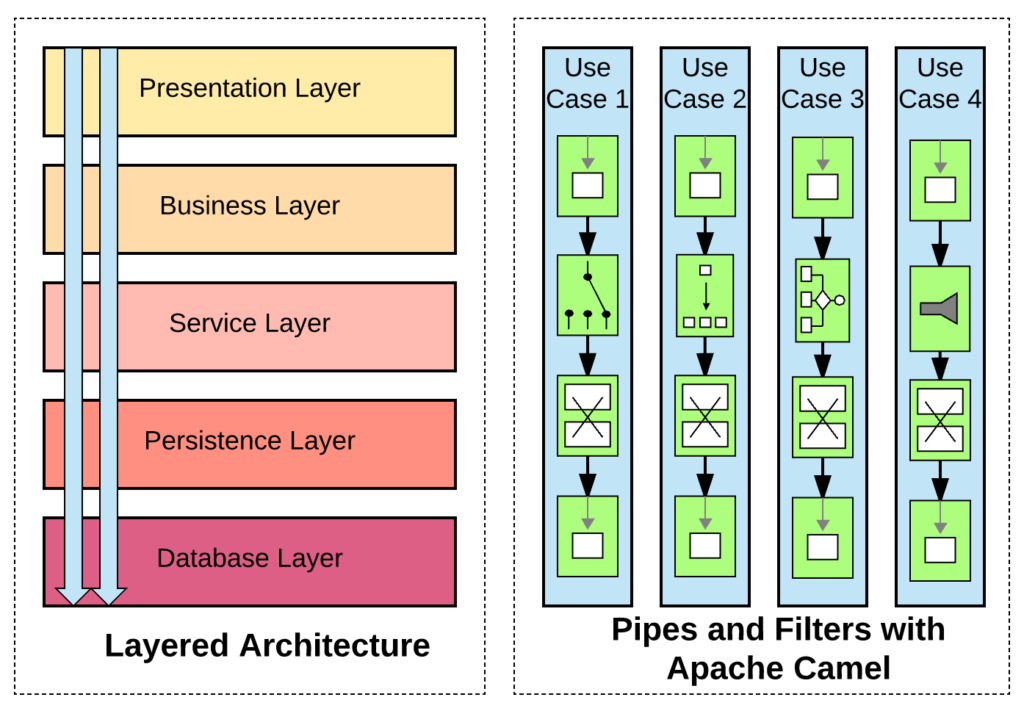

Let’s look at the two extremes: a layered architecture manages the complexity of a large application by decomposing it and structuring into groups of subtasks of particular abstraction level called layer. Each layer has a specific role and responsibility within the application and changes made in one layer of the architecture usually don’t affect the components of other layers. In practice, this architecture splits an application into horizontal layers, and it is a very common approach for large monolithic web or ESB applications of the JEE world.

On the other extreme is Camel with its expressive DSL and route/flow abstractions. Based on Pipes and Filters pattern, Camel would divide a large processing task into a sequence of smaller independent processing steps (Filters) connected by a channel (Pipes). There is no notion of layers that depend on each other, and in fact, because of its powerful DSL, a simple integration can be done in few lines and a single layer only. In practice, Camel routes split your application by use case and business flow into vertical flows rather than horizontal layers. And a typical Camel application is composed of multiple independently working Camel routes that collaborate for achieving the common business goals.

Layered architecture compared to Pipes and Filters pattern

As mentioned previously, when working with Camel, services created with it tend to end up as a single layer. Whereas this is fine for most of the simpler cases, applying the hexagonal architecture principles will help with creating better applications when working on large-scale projects. What I mean by that is, split your Camel routes into two layers that represent the inside and the outside of the application. The inside of the application is represented by Camel routes that implement the business logic of your integration and intended to be reused by multiple other routes and protocols. The outside of the application would be implemented by Camel routes that are the adapters in the hexagonal architecture i.e. routes that provide technology-specific logic e.g. handle a specific protocol, error handling logic specific for the endpoint, transactional and recovery actions specific for the endpoint as well.

How to Map Hexagonal Architecture to Camel?

Identify the inside of your application

Even the simplest services created with Camel have business logic. Usually, that is a combination of transforming data, content-based routing, filtering, splitting, aggregating, etc. Very often, none of the out-of-the-box enterprise integration patterns will be applicable and you will have to use your own custom Java bean as part of a Camel route. The awesome part is that Camel is completely non-intrusive and you can develop, test and use Java beans in Camel routes with absolute no dependency on the Camel APIs. Camel bean component will make sure that the bean method parameters are populated with the correct values and also take the return value and put it back into Camel routes.

If you have identified the routes containing the elements mentioned above, typically these represent the inside of your application. These kinds of routes should not contain logic that is technology and protocol specific. For example avoid using data that is directly populated by components, such as HTTP headers, JMS headers, and also error handling retry logic common for the HTTP protocol, compensating action logic, etc. Instead, keep this inside Camel routes focused on the business logic only and isolated from outside Camel routes.

Isolate the inside from the outside

In the hexagonal architecture, the inside of the application is reached through ports that abstract conversations. The Camel direct component is the perfect implementation of a port. It provides the synchronous invocation, the same as a method call in Java. It is not technology and protocol specific, there is no specific data format or schema validation requirement and can be used to pass in and out any kind of data. Typically, the preferred data format to pass is a POJO as it is the easiest and most flexible structure to manipulate in a Camel route. But if in your domain, the primary data format is XML, JSON, or anything else, you can keep to such a format as well. No strong rules to follow, but whatever works for you. The only thing that is fixed with a direct component is that it is a synchronous interaction model and I think that is the correct one by default. If asynchronicity is required, rather than using SEDA component for a port, it would be better to implement asynchronous logic either as part of the outside route (if asynchronicity is required by an adapter) or in the inside route if it is part of the business logic. But don’t limit the port to asynchronous model only.

A port represents a meaningful conversation in the context of a service. That in Camel is represented by a direct component, which is identified uniquely as a String value in the context of a JVM. One would think that direct component was implemented as a response to Alistair's port definition.

Keep outside out

So, we have the business logic of our application implemented as Camel routes accessible only through direct component endpoints as ports. Such a setup allows testing, reusing, and exposing the business logic over multiple protocols to the outside world using other routes. The outside of the application contains any logic that is dependent on the endpoints. Nowadays most common of these are the messaging or file based on asynchronous interaction, and HTTP based on synchronous interaction. But it can also be any of the other over 200 connectors that are present in Camel. Keep in mind that the components you use for the outside, are not only dictating the interaction model, but also usually define the data format, the transaction semantics, the error handling logic, and potentially even other aspects of the applications. For example, a SOAP endpoint will perform a schema validation, but consuming a JMS message will require an additional validation step. A transactional endpoint will perform rollback in the case of a failure, but a non-transactional endpoint will require a recovery action, an idempotent endpoint will allow retry, and a non-idempotent endpoint will not. I have described these kinds of considerations and other related Camel use cases in more details in the Camel Design Patterns book.

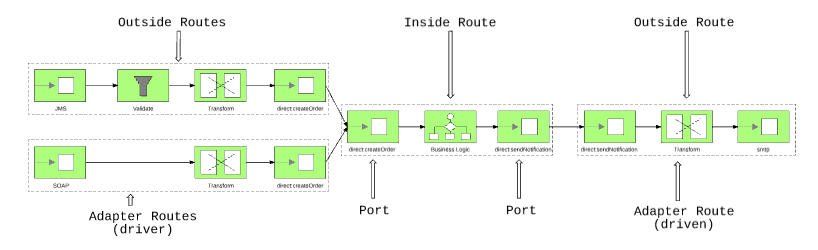

Putting it all together, a Camel based service that exposes some business functionality over SOAP and JMS is visualized below. The same business functionality is accessible through direct component for JMS and SOAP-based routes. Also, on the right-hand side, the same route is using an email notifications port and adapter for sending emails.

Ports and Adapters based Camel service

Notice that, outside routes are not only on the consumer side, they are also on the producer side, i.e. routes that send messages to other systems (remember driving and driven ports/adapters). The intent of the outside routes is to represent the various adapters that should handle everything that is outside specific: protocol, data format, and additional logic specific for the endpoint. In addition, an outside route should prepare the data in a format that is expected by the port by populating expected headers and the message body. This would allow the same port to be reused by multiple adapter routes. This includes also test fixtures in Camel for unit testing Camel routes, and even the error handling code. The error handling constructs in Camel (no doTry, doCatch, doFinally, but the onException construct) is actually representing a port that is automatically called by the framework on different types of exceptional conditions. Such a concept doesn’t exist in the Java language, but in Camel, it is a very commonly used execution path for unhappy scenarios. And treating the error handling flow as just another port in your application (even if it is not called by you but the framework on a certain occasion), will help you to reuse it for common error handling across multiple Camel routes.

In Summary

There are no clear rules or guidelines on how to compose an application with Camel routes. Defining those at design time usually limits the creativity of developers at implementation time, and not having guidelines can be a recipe for spaghetti architecture. In this line of thought, I think hexagonal architecture is sufficiently lightweight, doesn’t kill creativity and imagination during implementation by forcing specific structure. At the same time, it provides just enough guidance for structuring routes. And the best part is, it naturally fits the Camel-programming model.

My suggestion would start with VETRO pattern (Validate, Enrich, Transform, Route, Operate), and then apply hexagonal architecture style (Edge Component Pattern as described in Camel Design Patterns book). This is a good starting point for structuring Camel routes for the happy paths. Then pay special attention to achieving data consistency with the various error handling and recovery patterns. And don’t forget, there are no best practices, but only good practices in a context. Focus on your context and Camel will be on your side.

About the author:

Bilgin Ibryam is a member of Apache Software Foundation, integration architect at Red Hat, a software craftsman, and blogger. He is an open source fanatic, passionate about distributed systems, messaging and application integration. He is the author of Camel Design Patterns & Kubernetes Patterns books. Follow @bibryam for future blog posts on related topics.

To build your Java EE Microservice visit WildFly Swarm and download the cheat sheet.